|

|

本帖最后由 banmadanba 于 2014-6-29 23:13 编辑

Joining Study and Practice

Intellect and intuition both play an important role, so you cannot negate either of them. You cannot purely rely on meditation practice alone, without experiencing a sharpening of your basic intelligence, and in order to understand the sense behind the words, you have to have personal meditative experience. So those two approaches are complementary.

BUDDHIST TRAINING combines meditation and study. Throughout the path, learning and comprehending basic Buddhist teachings is as important as meditation practice. Since you are not going to spend all your time alone, all by yourself, you should be thinking in terms of helping others sooner or later. In fact, you should expect it. And in order to help others, study is important. For some practitioners, intellect is regarded as secondary(次要的) and rather worldly. Such practitioners just sit and practice meditation in a purely intuitive style. But intellect and intuition both play an important role, so you cannot negate(否定,取消) either of them. You cannot purely rely on meditation practice alone; you also need to sharpen your basic intelligence, and in order to understand the sense behind the words, you have to have personal meditative experience. So those two approaches are complementary.

Learning and practice are the essence of the Buddhist way. The mark of practice is a lessening(减少) of the kleshas, or neurotic thought-patterns. In mindfulness practice, your concentration is a very thin, sturdy(坚固的) wire going through all your clouds of thoughts. The practice of going back to the breath, back to reality, is taking place all the time. So it is very necessary for you to practice mindfulness utterly and completely.

The mark of learning is gentleness(亲切,温顺)). It is being tame(驯服的,平淡的) and peaceful. So learning is not purely academic. Proper learning requires an attitude in which you are not intimidated(被吓到的) by the presentation of Buddhism. You are neither too enthusiastic(热衷的,热烈的) about understanding Buddhism nor are you too disinterested. You might think, “I couldn’t care less(根本不关心) about scholarship(学问). I just want to sit and make myself a good Buddhist.” But that’s not quite possible. You cannot become a real, good, enlightened person if you do not understand what your life is all about. With gentleness, what you study becomes part of your psychological geography(地形). You can understand topics fully and thoroughly without having to push(努力做,下功夫). You can know what Buddhism is all about, and you can have some understanding of where things fit within this big soup of Buddhist intellect.

How to be in your life is meditation practice; how to understand your life is scholarship(学术研究). That combination comes up in ordinary life as well. For instance, eating food is meditation practice, and talking about how to cook that food is scholarship. So those two factors work together. If you rely on sitting practice alone, quite possibly you could become just a stupid meditator. But if you study too much and don’t meditate enough, you could become busy-stupid, without any essence(本质) or purpose(目的,目标) to your life. So both sides are important, both the heart and the brain.

The great Buddhist educational institutions of the past like Nalanda University(那烂陀佛学院), Vikramashila University(戒香佛学院), and Samye Monastery(桑耶寺)(Nalanda and Vikramashila Universities were centers of Buddhist and worldly studies in North India. Samye Monastery is said to be Tibet’s first monastery and university.) developed the educational approach called turning the three wheels: the wheel of meditation, the wheel of study, and the wheel of activity. Those three principles are constantly interlinked—they are the wheels that carry you on the path of enlightenment. Buddhist teaching deals with your own basic being. Nothing is regarded as a foreign element or non-Buddhist. Whatever the subject matter, the object of learning is to develop a higher, more sophisticated(高级的, 复杂的) way of thinking and of viewing the world. The object is to produce scholars who are at the same time great yogis(瑜伽士). By studying and practicing properly, you could influence yourself and your fellow sentient(有感知能力的) beings. That seems to be much more compassionate(慈悲的) than simply snatching up(抓起来) knowledge or running into the mountains and finding yourself enlightened.

The Buddha had a basic Indian secular(世俗的,非宗教的) education and he had knowledge of Hinduism, but that was simply his cultural heritage. In essence, Buddha’s mind is enlightened mind. When such a mind speaks, it is almost inconceivable(不可思议的,非凡的) for ordinary people. It cannot be compared with even the greatest wisdom of Western psychologists or scholars. The mind of the Buddha is sophisticated, spontaneous(自发的,自然的), and vast.

The Buddha’s learning is inconceivable. The Buddha knows the best way to boil an egg, as well as how to develop enlightenment on the spot(立刻,当场). His mind encompasses(包含,覆盖) everything. Such a mind is not divided into intuition and intellect. However, what Buddha taught has been categorized. His disciples wrote down everything he said, so the Buddha’s teachings have been passed on. At one of the early sangha conferences, his disciples(信徒) decided to categorize the Buddha’s teachings into vinaya(毗奈耶, 戒律), sutras, and abhidharma: monastic vows(发誓, 誓言) and discipline, discourses(会话) and dialogues, and philosophy and psychology. However, those categories are simply different aspects of the mind of the Enlightened One.

Proper training consists of practice and study put together. When you practice properly, you also begin to develop a state of mind that allows you to study properly. This twofold system of study and practice is very, very old. We used this system in Tibet, and it was also used quite a lot in India. Traditional monastic discipline consisted of alternating(交替的) periods of practice and study. Nalanda University and Vikramashila University, among others, used this twofold system to train people’s minds and at the same time develop their intellects. In turn, those ancient centers of learning produced great teachers and scholars like Padmasambhava(莲花生大士), Atisha(阿底峡), and Naropa(那若巴). Maybe you could be one of those people!

Usually when you go to a college or university, you cannot study properly because you are always being interrupted by your own subconscious(潜意识) gossip, your own background noise, and the feedback of your own neurosis. You have problems learning because so much interference(干扰) and so many interruptions are taking place. An ideal educational system allows for a period of time in which you can simply work with your state of mind. Then when you are ready for it—and even if you think you are not—you have a period of time in which to launch into study. In that way, you can actually grasp what you have been studying and practicing. You can learn about yourself and your mind, and you can learn about how things work in your life and in your world. Elucidating(阐明) those things is what the study of the Buddhist path is all about. Learnedness is not enough. You should practice what you preach(布道), take your own medicine.

Buddhist education is based on what is known as threefold logic, the threefold thought process of ground, path, and fruition(完成,成果). Threefold logic is very simple and straightforward; however, as you get into more difficult subjects, it becomes more subtle(微妙的,精细的) and complex. An example of threefold logic is:

Since I saw a completely blue sky this morning (ground),

It is going to be a sunny day (path);

It is definitely going to be a hot one (fruition).

In this example, the ground is blue sky, the path is sunny day, and the fruition is a hot day. So threefold logic is very simple: it is the process of coming to a conclusion.

THE ROLE OF PRACTICE

The discipline of mindfulness, or shamatha, should combine practice and study in the fullest sense. Shamatha is not related with sitting practice alone; it is also connected with how we learn and absorb the teachings of the Buddha intellectually. Shamatha practitioners are able to understand the technical information taught by the Buddha; they are able to hear the dharma. So shamatha is an intellectual tool as well as a practice tool. Shamatha is an intellectual tool because it allows us to hear the dharma very clearly; it is a practice tool because it allows us to quell(消除) mental disorder. When we have no mental disorder, we are able to learn. Therefore, dwelling(住所,居住地) in the peace of shamatha discipline is necessary for both study and practice. However, by peace we do not necessarily mean tranquillity or bliss(极乐). In shamatha, peace is orderly comfortableness. It is orderly because the environment is right; it is comfortable because you are using the right technique to control your body, speech, and mind. Therefore, fundamental decency(体面,正派) takes place. In short, shamatha could be referred to as that which cools off intellectual obscurations(遮蔽, 昏暗) and psychological disorders.

Shamatha is the beginning of the beginning of how to become a practicing Buddhist.3 Shamatha practice is essential(基本的). Unfortunately, many Tibetan teachers teaching in the West do not emphasize shamatha practice. Perhaps this is because in Tibetan culture, when people requested training, they had already been raised in a Buddhist nation by Buddhist parents, so they were familiar with mind training as a natural process. But according to everything in the Buddha’s hinayana, mahayana, and vajrayana teachings, there are no other options. The only possibility is to begin at the beginning, and the one and only way to do so is through shamatha discipline. Therefore, we have to get a grasp on the teaching of shamatha, and understand that discipline as much as we can.

Thinking Dharmically

Dharma is not once(一次也不) removed. You start from the immediate situation, your mind and body, and you work with what you have. You start with sitting practice and with your pain and anxiety. That’s good! That’s the best! It is like the fuse of a cannon, which first hisses, then goes boom! You can’t make a fuse out of crude gunpowder. It has to be ground into refined gunpowder in order to coat the fuse and ignite the cannon. In the case of shamatha practice, basic anxiety becomes the refined gunpowder that allows you to set a torch to ego-clinging so that your cannon can go boom!

There is no medicine, no surgery that will make it easy for you to study and practice the dharma. It is hard. However, once you realize it is hard, it becomes easy. Practice instructions do not come along with suggestions such as “Take two aspirins, and then you can do it” or “Have a few shots of Johnnie Walker Black so that you can jump in.” Advice like that doesn’t help. You just have to do it. There is no service that helps you to get into dharma practice easily—if there were, it would be terrible. That would not be true dharma, because you would not have to sacrifice even one inch, one discursive thought. You would be blissed-out on the dharma, or on enlightenment, which is impossible. In true dharma, hard work and really diving into it bring further cheerfulness. You realize that you have dived in and you have no other choice—but it feels so good to do that.

We practice meditation so that our mind may be one with the dharma. Becoming one with the dharma means that whatever you think, any flicker of thought that occurs, becomes a dharmic thought. That is why we practice meditation, so that our mind could become like that. When your mind is one with the dharma, you don’t have to say, “Now I’m being bad and now I’m being good” or “Now I can switch into being either wicked or good.” If your mind has become one with the dharma, you naturally begin to think dharmically.

Thinking dharmically does not mean you always think religious thoughts or that you become a holy man or a holy woman, a monk or a nun. It means that you become a mindful person. You watch every step that happens to you. You are trying to be a decent lady or gentleman of the world. Being one with the dharma is based on natural ethics. You don’t do things at the wrong time or in the wrong way, and you don’t mix good and bad together. You have respect for the world as well as for your own mind and body and their synchronization. You have respect for your family, for your husband or wife, and your children, if you have any. One of the fundamental obstacles to becoming one with the dharma is the delusion, anxiety, and ignorance that result from samsaric neurosis. In order to overcome that obstacle, it is necessary to practice shamatha, and in order to practice shamatha, you need to reorganize your life.

Buddha said that the dharma should be an antidote for desire, that dharma means taming the mind and being free from desire. Where did desire come from and what has to be tamed? Desire is anything that causes us to look for something other than what we normally perceive. In contrast, normal perception is just a simple business affair. We are simply seeing red, simply seeing green, simply seeing white. We are simply drinking a hot cup of tea, as opposed to looking for something to help us cure our pain, ease our loneliness, or fulfill our passion or aggression. Desire is the excess baggage of mind. So in order to tame desire, the mind has to be tamed. Therefore, sitting practice is known as the practice of taming: we are taming ourselves.

APPENDIX : WORKING WITH THREEFOLD LOGIC

Judith L. Lief

INTRODUCTION

Working with threefold logic is a way to study the teachings with clear-headedness and an understanding of how things evolve(发展). In studying the dharma, you are relating with your own mind rather than simply learning a philosophy or psychology. Therefore, your approach should be simple and direct. It should be gut(直觉的, 内部的) level, with no compromises(妥协).

Threefold logic is based on respect for language and an awareness of how language can create a state of mind. It is based on the idea that speaking dharma, or truth, is sacred. Trungpa Rinpoche said that his own talks always followed threefold logic, so an understanding of that approach is helpful for studying his teachings. But threefold logic cannot be forced or applied(应用的) mechanically. If you try to force it, it becomes a way of complicating rather than simplifying. It begins to promote conceptual mind rather than directness and clarity of thought and expression.

The basic approach of threefold logic is to take a theme, elaborate(复杂度, 精密的) on that, and make it solid. One way of doing so is in terms of ground, path, and fruition, with ground as the basic perspective, path as how you practice that, and fruition as realization. However, there are other possibilities. You could use the logic of definition, nature, and function. Here you begin by defining what you are talking about, then you discuss its nature, and how it functions. If you are discussing water, for instance, you might say that it is defined as a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen, that its essence is wetness, and that its function is to quench thirst. Another variation is to think in terms of essence, cause, and effect. For instance, you could say that the essence of a vegetable is its nutrients, its cause is that it was planted and nurtured to maturity, and its effect is to satisfy hunger.

In thinking about a topic in terms of threefold logic, there are two basic paradigms(范例). In the first, you examine what is happening now and see how it arose, starting with step three and working backward. In the other, you examine what is happening now and see where it leads, starting with step one and working forward. In the first paradigm, for example, you might begin by observing that you are feeling sad (fruition). You then look back to find that the ground was a bad dream, and the path was responding to that dream as if it were real. In the second paradigm, you again begin by noticing that you feel sad, but this time it is the ground. You go on to see that the path perpetuating(使继续) this feeling is self-pity(自怜,自哀), and the fruition is depression.

EXAMPLES

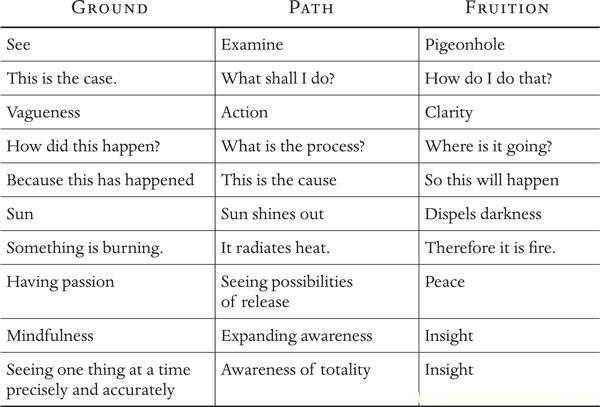

The following chart contains additional examples of threefold logic, which may help you get a feel for the process.

|

|